With the rise of Christianity in the Middle Ages, the monks codified winegrowing and turned it into a trade. Gradually, the wines of Bourgogne became a major political and economic asset. As an instrument of power and prestige, they were enjoyed across the whole of Europe under the reign of the powerful Dukes of Bourgogne who turned them into gifts of choice.

The monastic rules of Saint Bernard, the perfect environment for working the vines.

In the 12th century, Abbot Bernard de Clairvaux imposed strict rules on the Cistercians, which alternated labor and prayer. Under the influence of these rules, the monks carried out some phenomenal work improving their vines and their farmland.

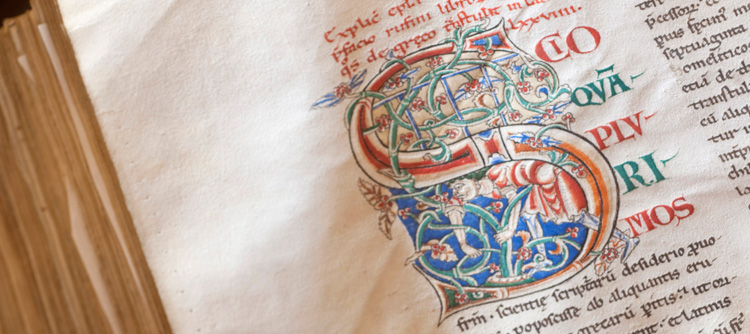

They applied new vinification techniques and recorded the results of their experiments in detail. To this day, that written heritage contributes to the notoriety and the preservation of the terroir of Bourgogne.

The Hospices de Beaune and its vines – a Medieval gem

The Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune (or Hospices de Beaune) was built in 1443 by Nicolas Rolin, chancellor to Philip the Good. This hospital for paupers had its own vineyards, which provided it with an income. This estate grew over the centuries, as the hospital was bequeathed various plots or money.

Today, when you travel to Beaune, you can visit the Hospices’ superb flamboyant gothic buildings. They have been wonderfully preserved, and now house a fascinating museum.

These days, the wine made from the Hospices’ vineyards is sold each year at auction on the third Sunday in November to raise money for Beaune Hospital and the Hospices museum.

In the Middle Ages, Christianity was on the rise across the whole of France. Wine then became a sacred drink, symbolizing the blood of Christ. It was a key element in the celebration of Christian rites.

During this time, religion was very important, and bishops and monks had a growing role in society.

The religious communities of the Bourgogne region received gifts from local nobility, often in the shape of land. They established huge estates, which they then enlarged by buying up neighboring plots. The biggest estates were held by two communities:

Founded with the Abbey of Cîteaux in 1098, this order held land on the Côte de Beaune and Côte de Nuits, as well as plots near Chablis and Chalon-sur-Saône.

Created with the Abbey of Cluny in 909, the Cluniac Order was another major landowner on the Côte Chalonnaise and the Mâcon region. It also owned some vineyards farther north, including the current plot of Romanée-Saint-Vivant.

The monks used their land to firstly produce the wine necessary for the celebration of mass. Gradually, through their hard work, they developed the art of winegrowing, improving both quality and yields. As such, they were then able to sell some of their wines. And by the 15th century, the quality of their wines was recognized across Europe. Each abbey and each monastery made certain to maintain the very highest quality production to ensure their reputation.

During this Medieval period, often troubled by war, the monks enjoyed a certain peace. They honed their unique winegrowing expertise, improving it and handing it on from generation to generation. Their rigorous methods covered all aspects of winegrowing, from pruning to comparing and selecting varietals, and preserving their wine. But above all, these religious communities were responsible for establishing the bases for two fundamental notions for the identity of the terroir:

These are precise plots of land, marked out according to the nature of the soil and the local climate. These plots produce wines of different character, carefully classified by the monks depending on their quality. Today, in Bourgogne, you can find thousands of Climats, some of which enjoy an international reputation.

These are Climats surrounded by walls, constructed by the monks to protect their vines from animals. These clos shaped the landscape of the Bourgogne region. They also embody the continuity of local tradition: between the Middle Ages and the Revolution, some of them only had one or two owners.

From the 14th century onwards, the Dukes of Bourgogne, as owners of many vineyards, enjoyed great economic and political prosperity. Wine was about power and wealth, a symbol of taste and refinement.

To preserve this prestigious reputation, the Dukes developed the first wine and vine-related policy in history. In 1395, Philip the Bold issued an edict that provided the basis for the production of quality wine, with the health of the consumer as a priority. His edict involved two key decisions concerning the wine varietals to be cultivated in Bourgogne:

This generous and resistant varietal was very popular in the Middle Ages, making an everyday wine that was produced in abundance by small winegrowers. The people liked it but the wine was criticized by the powers-that-be. They feared it compromised the quality image of Bourgogne wines they were trying to promote. This ban covered Bourgogne of the day, and as such, did not extend to the modern-day Mâconnais.

This varietal offers lower yields and results in more complex wines, which were exported outside the Bourgogne region. Philip the Bold was a big fan.

This development gave a boost to the region and improved the quality of its wines. Its influence grew and soon, Bourgogne wines were being served at the tables of the King of France and the Pope, in Avignon.

This prestigious beverage was a powerful political asset and the Dukes knew how to use it. In 1429, Philip the Good founded the chivalric Order of the Golden Fleece in Bruges, to help the spread of Catholicism, and Bourgogne wines were the favored drink of its knights.

Similarly, this elite wine flowed bountifully at the Feast of the Pheasant, a major diplomatic event also hosted by Philip the Good.

From there, Bourgogne wines gradually conquered all of European high society, from the nobility to the bourgeoisie, opening up some formidable sales opportunities.

In parallel, regular winegrowing continued to flourish in the region, producing wines for the ordinary people and minor bourgeoisie in the towns.

Despite the edict of 1395, people gradually returned to growing Gamay. It maintained a strong foothold in Bourgogne until the introduction of the Appellations d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) system in 1935. At that moment, the reorganization of the Bourgogne region favored the Chardonnay and Pinot Noir grapes, which now represent over 80% of all vines planted in the region.